Little Star, from left to right: John Value, Julian Morris and Daniel ByersWalking into Taste Tickler feels like a blessing after having navigated through the maze of holiday drivers around Lloyd Center. The small sandwich shop is deserted, save for a few employees in the backroom; I settle at a table fettered with age. The wall behind it displays a series of posters featuring Clark Gable and the Marx Brothers. There isn’t much of a wait before Daniel Byers, the lead vocalist and guitarist for Portland band Little Star, arrives at the shop to join me.

Little Star, from left to right: John Value, Julian Morris and Daniel ByersWalking into Taste Tickler feels like a blessing after having navigated through the maze of holiday drivers around Lloyd Center. The small sandwich shop is deserted, save for a few employees in the backroom; I settle at a table fettered with age. The wall behind it displays a series of posters featuring Clark Gable and the Marx Brothers. There isn’t much of a wait before Daniel Byers, the lead vocalist and guitarist for Portland band Little Star, arrives at the shop to join me.

Following shortly thereafter is vocalist and bassist Julian Morris. Both sit directly across from me, waiting for their orders to come, making small talk to mask the time before drummer John Value’s arrival.

Genuinely polite and soft-spoken, both Byers and Morris strike me as the antithesis of Portland’s DIY punk scene. They laugh at one another, aiming to relate rather than hurt. They discuss their work as if in private, wondering when practice should take place, among other things. After a few moments, Value walks to our table in a cool, unhurried strut.

Everyone eventually settles in. “Do you want to hear a fun fact?” Byers asks, breaking the ice with mild-mannered humor.

“Do we want to know if you’re fat?” Morris quips.

Laughing, Byers continues. “No, a fun fact. Usually during an introduction, you do a fun fact, right?” Hesitating, he stops to think over his answer. “Um…”

“Dude, you’re supposed to have one,” Morris jokes.

“I know, this is bad. Okay. In college, whenever I had to do this, I would say I was trilingual,” Byers stops to find the right words. “I’d say I could speak Spanish, Chinese and English. Inevitably, someone would come up to me and speak one of those languages, making it clear that I was not trilingual. All of those years, I had that fun fact to use, but it’s false, so…pass.”

The group laughs, allowing enough room for nerves to dissipate. Morris refuses to offer anything and passes the torch to Value, who jumps at the chance to share his story. “One time I hugged Iggy Pop, but he wasn’t wearing a shirt. His skin was like tanned leather. It was during a show and he wasn’t sweating because his skin is like cowhide.”

“He’s been shirtless for so long, his skin must be a callus,” Morris interrupts, and Byers gives short laugh in reply.

Amidst the residual clattering from the shop’s backroom, customers pour through the entrance and gradually fill the tables around us. Value, having arrived later than the rest of the group, leaves temporarily to grab himself some food. Despite this, Morris continues, pointing to Byers. “You want to know how Little Star was formed? He originally started the band,” he says.

Byers stops mid-bite to expand on the subject. “It started as my recording project that I did on my own with drum machines and stuff, just me. Julian and I had been in each other’s lives through music, but we were in different bands at the time. I’ve always looked up to [Morris] as a musician, and I just asked him to come and start playing with us. It was just really random, but [Value] started practicing with us and it was beautiful. He was really good. I remember, at the end [of that first session in the summer of 2015], he said he felt lucky to be playing with us. Since then, it’s been going really well.”

“Dan was in a great band called Eidolons for, I don’t know, four years?” Morris adds, and Byers nods his head as confirmation.

“I played in a couple of bands, most notably with a local group called The Mucks,” Morris continues. “We did one tour together in 2012. Dan and I had always been in shows together, but never in the same band. We fawned over each other from a distance. Both he and I were busy with other projects, so we had never played with one another. Then, Eidolons slowly came to an end, as did the project I was in. That’s how Little Star came together.”

At this point, Value returns to the table and pauses to catch up on the conversation. “I was moving around a lot [for] about five years before I came to Portland,” he says. “I was mostly just traveling and recording music, but I was also looking for a project where I could relate to the people in it. Little Star is the first band where that’s happened since, like, high school. I was just a wanderin’ dude waiting to get snatched up, and they snatched me on up,” he muses in a fake Southern accent.

Once the group had officially formed, the real work in realizing Being Close began.

Once the group had officially formed, the real work in realizing Being Close began.

“These are songs that Julian and I wrote. My songs are about being close to people and not just the good parts, but also feeling like you’re moving apart from someone. Pretty standard whiney rock music,” Byers jokes.

Being Close, at its core, is an objective analysis of how distance plays an essential role in the dissolution of a relationship. Ranging from cynical riddles laced with anxious and aggressive melodies, to simple observations of bonds rotted from within, Little Star frustrates the chance of optimism seeping into any of the songs just by keeping things realistic. These aren’t love songs. Rather, they’re messy examples of when the unexpected screws with our ideals. Byers excels in feeding this front with unusual bursts of expression, as heard in songs like “New TV.” Yet despite these bursts, he still retains the mask of indifference toward the subjects at hand.

“It’s not really hurt or anything; it’s just that feeling of moving apart,” Byers explains. “I meant to represent the absence of something. There’s no goal of depicting bad feelings, or even good feelings necessarily. There’s just nothingness while trying to think about how complex it is to drift apart from someone.”

“I feel like Dan has this amazing way of saying something, yet meaning the exact opposite. You can really hear what he’s expressing, but without him being outright,” Morris adds. “Our music can be loud and intense, but it’s about having intimate feelings about being a person and interacting with others.”

The title track and the album’s opening song, “Being Close,” holds true to Byers’ statement. “I want you to be happy / even if that means you act like you just met me,” he says, lingering in near whisper, forcing his voice to adopt a desperate plea yet failing to get the emotions to match the meaning of his words. In spite of this indifference, Byers’ emotional discontent is notoriously blunt. His words are kept to a minimum, but they’re stated in such a way that his overarching message slaps you across the face by the album’s end.

Yet, the only two songs written by Morris differ entirely from the style Byers relays. Both “Voice” and “Hungry Ghost” could stand alone as testament to those looking to create new identities. In Morris’ case, his impression comes from a more physical route.

“I identify as a trans man and those songs are both about the past year in my life,” he says. “I had been transitioning and started hormone therapy, a process that changed my voice and dropped it significantly. 'Voice' was a song I wrote at the beginning of that [process], knowing that it had a very distinctive timeline. The chorus is essentially saying I’m giving my voice to this process I’m going through.”

Morris pauses. “I actually can’t sing that song anymore since the timeline has passed, but it was a really cool experience to be that cognizant of my changes as I was singing the song and letting everything happen,” he continues.

The album’s closing song, “Hungry Ghost,” pays homage to the allegory of one rising from the ashes, a likeness to the physical rebirth Morris underwent. “The song is just about, you know, getting to the point where I could own this identity and be a trans person in this world. There’s a persistent thing that’s telling me I have to do it. The song starts with a new, indescribable feeling, but the way 'Hungry Ghost' ends, it’s just so sparse. Yes, it’s me admitting to this thing, but the result becomes this celebratory, soulful experience. Like, I’ve accepted myself and I’m just fucking doing it.”

“Then you get to dance,” Value adds.

“Yeah!” Morris laughs, loud enough for others at surrounding tables to look up from their meals. “It’s a danceable experience, for sure.”

“Apart from what [the songs] are about, I feel like the process of making them is cool. Really, the most exciting part is watching how the songs transform,” Byers says, transitioning into the technical talk of creating Being Close.

Having recruited Mac Pogue (Alien Boy, Drunken Palms, Snow Roller) as the engineer, the trio chose to record the bulk of Being Close live in a single 18-hour session at Portland’s Type Foundry Studios. From there, the effort in creating this album took a hands-on approach and thus sparked conversation regarding the band’s DIY roots.

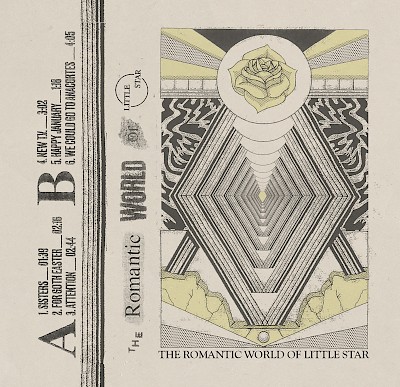

Little Star's debut cassette, 'The Romantic World of Little Star'“I don’t know, DIY is kind of a funny term,” lingers Byers on the idea of fitting into a DIY style, considering the music initially began as a bedroom recording project, which led to the self-released cassette The Romantic World of Little Star. “To me, it sometimes doesn’t really mean that much. We did do [this album] ourselves, but we recorded it in a studio with our friends.”

Little Star's debut cassette, 'The Romantic World of Little Star'“I don’t know, DIY is kind of a funny term,” lingers Byers on the idea of fitting into a DIY style, considering the music initially began as a bedroom recording project, which led to the self-released cassette The Romantic World of Little Star. “To me, it sometimes doesn’t really mean that much. We did do [this album] ourselves, but we recorded it in a studio with our friends.”

“We did do it in a studio, but we did it in almost a guerrilla way,” Value interjects. “It’s cheaper to bring in your own freelance engineer, so we chose Mac. He’s a really good friend, and we basically reaped the benefit of being in a high-quality studio. It could have been intimidating working with an expensive engineer, but we subverted it and made it with our buddy. Then, we mixed it in our basement and we were going to have it out anyway before our friends in Good Cheer came along. So, in that way, it’s DIY because we’re not waiting for someone to come along and take care of things for us.”