“I THINK PEOPLE GIVE A SHIT HERE—I REALLY DO,” SAYS A SOFT-SPOKEN MAN WHO’S SPENT HIS FAIR SHARE OF TIME IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY, LIKELY WITNESSING PLENTY OF PEOPLE WHO DON'T.

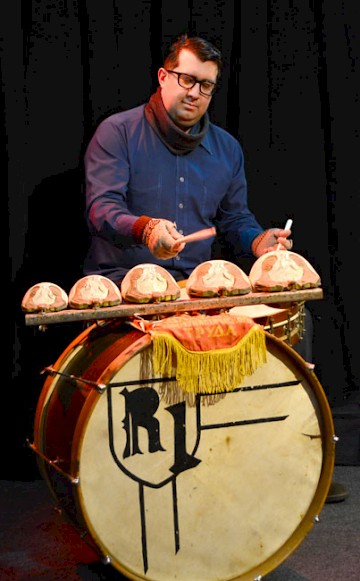

Jose Medeles: Photo by Franklin HillToday, Jose Medeles runs NE Portland’s Revival Drum Shop and makes percussive noise with drums and vibraphones in 1939 Ensemble, but he’s been playing professional since age 15, building an enviable resume that’s taken him around the world behind the kit for The Breeders and on stages with legends like Joey Ramone and Mike Watt as well as in studios with contemporary stars like Ben Harper.

Jose Medeles: Photo by Franklin HillToday, Jose Medeles runs NE Portland’s Revival Drum Shop and makes percussive noise with drums and vibraphones in 1939 Ensemble, but he’s been playing professional since age 15, building an enviable resume that’s taken him around the world behind the kit for The Breeders and on stages with legends like Joey Ramone and Mike Watt as well as in studios with contemporary stars like Ben Harper.

“I’ve achieved so many of my goals—so many,” he quietly emphasizes. “When I left Los Angeles, I knew what I was leaving and I was fine with that. I’m cool, you know what I mean? I’m totally satisfied. I feel really fortunate, but I sacrificed a lot.”

The desire “to concentrate on family and be a present husband and father” is what brought Medeles to Portland to settle down and start, what was at the time, the “smallest drum shop in the world.”

After years of touring through the Northwest and seeing Portland’s evolution, Medeles had an inkling of what the Rose City was like—“laid back” and reminiscent of his Midwest roots— but he had no idea of the community he would find here.

THE PROMISED LAND

It’s no secret that outsiders are flocking to Portland: More people moved to Oregon than any other state in 2013, according to United Van Lines’ 37th annual interstate migration study.

“Portland has a reputation all over the country,” says one Asheville native who just “wanted to come check it out.”

“People in Asheville know about Portland.” It’s renowned for being “artsy” with plenty of “different creative things going on” and “very green,” all of which led Sallie Ford to simply buy a one-way ticket from North Carolina to PDX. And after two nights at the Hawthorne Hostel in October 2006, “it stuck”—and here she is.

Even in the late ‘90s, a touring musician from New Mexico “found Portland to be incredibly fertile and supportive ground.”

Now recognizable by silhouette and stature, the ever-present Lewi Longmire and his “community of people” relocated to Portland because “it just seems like Oregon has always been the place where the dreamers and the people who were weirder and stronger seemed to go,” he laughs. “It’s always been attractive to folks who were willing to work a little harder to live the life they wanted to live as opposed to just putting up with whatever was around them.”

A Brush Prairie-born rock star from rural country north of Vancouver, Wash., has a similar theory: Since the early days, “this whole region was [full of] pirates and adventurers and pioneers. I think that attitude has carried on,” she says. “We were considered so remote in the beginning that we were always DIY and always had that punk rock attitude.”

“Everybody made music for themselves—not for a trend and not to have any commercial potential,” explains The Dandy Warhol’s Zia McCabe. “There was no commercial potential so that didn’t matter! Everybody just did what they wanted” and embraced a “freedom of expression that I don’t think many cities have.”

THE DIVERSITY DILEMMA

This openness, to experimentation and collaboration, is what continues to draw talent to Portland, even those who make music outside of the pervasive, guitar-slinging rock scene.

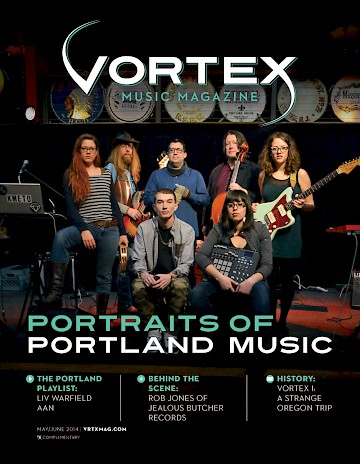

Zia McCabe of The Dandy Warhols, Lewi Longmire, Tope, Jose Medeles, Skip vonKuske of the Portland Cello Project, Natasha Kmeto and Sallie Ford from left to right: Photo by Autumn AndelWhile California transplant and electronic musician Natasha Kmeto doesn’t believe Portland’s music scene is incredibly diverse—“it’s pretty indie rock heavy”—the quality of the music and the musicianship trumps what she experienced in L.A. And this was something she promptly grasped.

Zia McCabe of The Dandy Warhols, Lewi Longmire, Tope, Jose Medeles, Skip vonKuske of the Portland Cello Project, Natasha Kmeto and Sallie Ford from left to right: Photo by Autumn AndelWhile California transplant and electronic musician Natasha Kmeto doesn’t believe Portland’s music scene is incredibly diverse—“it’s pretty indie rock heavy”—the quality of the music and the musicianship trumps what she experienced in L.A. And this was something she promptly grasped.

“I really wanted to get out of California and be in an alternative, arts-leaning community that wasn’t so much about commercialism of art and more about just art,” she explains. “I was considering Portland or Austin and I never even made it to Austin. I visited Portland once and fell in love with it.”

Portland-born and -bred emcee and producer Tope echoes Kmeto’s sentiments: “I don’t feel like there is a lot of diversity in Portland music. There is one genre that holds the reins and that’s the rock genre.”

Yet, this is still a very desirable place for these two to make music because the scene is so active and accepting. For musicians outside of the dominant rock scene, support from the mainstream has been forthcoming as both Tope and Kmeto have experienced crossover success. Kmeto has been able to “engage with people in that [indie rock] scene. We’re all from such different places but we’re able to come together and I think that’s really cool.”

“Most of the major success I’ve seen has been through the rock community,” Tope says. But he’s actively thrown himself into the rock scene, infusing his hip-hop craft with local indie rock—whether being signed to the Amigo/Amiga label, remixing rockers, or creating an entire album (the recent TxE album Vs PRTLND) based on Portland-made rock samples.

“Bands that are completely different musically than you still are open to being friends and playing random shows together,” Ford describes, while Kmeto adds that every artist she’s “shared a stage with or had a mixed bill of different types of music has been super cool and receptive.”

Musicians on every level of the totem pole seem to be very open and accessible. “I’ve met so many friendly people,” Ford says. “Even the people that are in big bands are usually really laid back and nice.”

A Creative Confluence

Portland’s little-big-town reputation also makes bumping into like-minded artists easy. “Everybody still goes out to the same bars,” Ford explains, while McCabe rattles off a list of the local performances that she’s seen in the past week: “They were all beautiful and authentic. Just being in Portland, where everybody’s a musician and creative and you’re constantly being inspired, that’s probably the most valuable thing.”

Click to read more stories from the debut issue of Vortex Music MagazinePortland-made music stands out because, even though it’s dominated by rock-based genres, “There’s a lot of diversity within the rock scene,” Tope says, “and that just comes from there being so many talented people.”

Click to read more stories from the debut issue of Vortex Music MagazinePortland-made music stands out because, even though it’s dominated by rock-based genres, “There’s a lot of diversity within the rock scene,” Tope says, “and that just comes from there being so many talented people.”

“The rock is never standard issue, the electronic is never standard issue, the hip-hop isn’t,” Kmeto emphasizes. “I think people are open to more avant-garde things here—the less cookie cutter you are, the better.”

In L.A., “you could go see any style of music, but it’s going to be whatever’s commercially popular in that genre,” Kmeto continues. There are niche scenes in L.A., “but everything feels more organic and underground in Portland as opposed to there being this big, blown-out commercial hierarchy and then the underground.”

Freedom means that talent has converged and thrived in Portland.

“The amount of quality musicians here doing so many different types of music and being able to do what they want to do—whether it be underground electronic noise, avant-garde jazz, Americana, singer-songwriter—I mean it’s crazy,” Medeles says. “It’s not like there a couple people doing it in each of those genres, there are scenes—it’s awesome.”

“You can just randomly walk into a bar and discover one of the best bands you’ve probably ever heard,” Tope says, illustrating the accessibility of quality music in Portland on any given night.

And while both Tope and Kmeto believe Portland has room to grow in terms of the genres that are represented, being flush with talent is one part of the Portland music industry. The other is “a fan base and consumers that actually want to partake in it, which I think Portland has in spades,” Kmeto says. “People go to shows here; they’re engaged.”

The Value of Music

“So much of America seems like if you give them something for free, they just assume it doesn’t have any value,” Longmire explains, “because: ‘It’s free? What’s wrong with it? Must not be very good.’”

“The biggest thing about Portland that seems different from other places is that the people, the audiences here, really sort of understand that they are getting something of value,” he continues. “Even though there are tons of venues that constantly have free music in Portland, people will go out to go see a band where they’re not being asked to pay for it and they will pull out money and stuff it in the tip jar to an extent that I have never seen anywhere else.”

To some degree, Portland audiences feel like they are a part of the same community as the musicians, not to mention the fact that they may often also be a part of the music-making community.

“In Portland, you give people something for free and they’re like: ‘We love it and we don’t want you to stop giving it to us so we will support it. We will give you money even if you’re not asking for it because we value you what you’re giving.’ There is that culture and that is amazing. It’s nice to see people who still value the amount of work that musicians put into doing their thing.”

Portland’s Music Industry?

Beyond receptive and supportive audiences, many local musicians point to the bevy of bands, venues, recording studios, record stores and indie record labels as evidence that there’s a bustling music industry alive in Portland today.

“There’s an underground or cottage industry of recording studios all over this city,” says Skip vonKuske, a cellist and founding member of the Portland Cello Project. “There are a few on this street that don’t have a storefront,” he reveals as he sits inside Mississippi Studios.

Zia McCabe of The Dandy Warhols and Portland’s "go to guy" Lewi Longmire catch up: Photo by Autumn Andel“Watching the development of Portland over the past 15 or so years, there’s definitely a music industry here now,” Longmire says. He cites a number of local bands “who make most of their money off of licensing deals and things like that” but is unsure of how the industry compares to major players like “L.A., Nashville, Austin or New York.” Still, “There definitely must be an industry because I’m seeing it happen to people I know—they’re able to support themselves.”

Zia McCabe of The Dandy Warhols and Portland’s "go to guy" Lewi Longmire catch up: Photo by Autumn Andel“Watching the development of Portland over the past 15 or so years, there’s definitely a music industry here now,” Longmire says. He cites a number of local bands “who make most of their money off of licensing deals and things like that” but is unsure of how the industry compares to major players like “L.A., Nashville, Austin or New York.” Still, “There definitely must be an industry because I’m seeing it happen to people I know—they’re able to support themselves.”

With two decades of experience as a working musician in Portland, vonKuske says, “I don’t know who’s the CEO or who’s running the front desk, but there’s an industry here.” He too points to numerous local musicians making a living off of music, but as vonKuske alludes to, it’s harder to pinpoint if there’s an organized industry behind the individual efforts.

As up-and-comers like Ford have often sought “labels, managers and booking agents that live other places” because technology easily facilitates that, she believes “the better industry and business stuff here is the venues, festivals and journalism, plus the filmmakers and photographers are really great too.”

This all sounds very familiar and wholly in line with Portland’s locally minded, DIY ethic. The music industry here is less of a business machine and more of a community where the sum of prolific individuals adds up to something that’s garnered attention outside of the city.

The existence of an industry also depends on your definition—or the level of services that you require. For The Dandy Warhols, their management is outside of Oregon. “I think we have a scene but I don’t think we have an industry,” McCabe says. “If you have something in Portland, it’s local. We don’t have that where the reach goes out to the rest of the world quite yet.”

Sustaining the Scene

If a visible, profitable industry isn’t sowing the seeds of success and sustainability, why do people keep descending upon Portland?

Three reasons: social acceptance, affordable quality of life and, most importantly, community.

Coming from Sacramento before L.A., Kmeto says “the artist’s lifestyle is less tolerated” there, “while everyone here is either a musician or a painter or they’re in film.”

Plus, there’s abundant openness to creativity. “I think there’s not as much judgement here,” Ford says. “It’s accepted to be a variety of genres, so I don’t ever really feel pressure about what kind of music I’m making for the Portland crowd,” which can lead artists to take risks.

For veterans like Longmire, McCabe and vonKuske who have been around the Portland music scene for several decades and witnessed its evolution, minimal overhead facilitates creativity.

A low cost of living can be an enabler: “Portland was a fairly cheap place to live on the West Coast, which made it easy to do your art and still make rent,” Longmire explains. It makes for “an easier existence as an artist,” Kmeto supports.

“There’s definitely a unique environment here,” Longmire says, “and I probably could not live the life that I’m living in any other city in America. That’s definitely something unique to Portland that I’ve been able capitalize on in my own quality of life.”

VonKuske believes that the cost of living plus “an abundance of flexible jobs allows you to work part time and then focus on your art side.”

“For me, there’s also a preponderance of venues,” vonKuske says. “Having a weekly gig with McMenamins is one of the things that allowed me to launch away from small parttime jobs to playing music full time.”

Space to Play

Whether musicians are “giving lessons, working at a coffee shop or opening a drum shop,” Medeles lists, many local businesses empower the artist lifestyle. “All of the businesses that I’ve dealt with, as far as collaborating on shows and projects, have been really excited and engaged,” Kmeto says.

“The environment here, at least for now, the bigger hands aren’t crushing everything,” Medeles adds. “There are still places to play your music and show your art, unlike a lot of places.”

“I don’t know the actual numbers, Longmire says, “but it felt like there were about 15 venues in 1997 and there are 50 now.” Which is exactly why younger artists like Tope feel like “The scene is wide open. There are so many opportunities and venues and people that are fans of music that it creates so many options. Anyone can walk in and step into the scene at any given point in time.”

Camaraderie

It’s a word Medeles keeps coming back to. “People really care about each other,” he says. “And the reason I can say that is because of Revival and ‘39 Ensemble. Thirty-nine is a drums and vibes and noise band that people come to see, places pay us money to play—you gotta be kidding me? That’s so amazing. Fucking Portland,” he summarizes, full of respect and awe.

Time and time again, local musicians mention the supportive the community that exists in Portland.

Natasha Kmeto, Lewi Longmire, Jose Medeles, Tope, Skip vonKuske, Zia McCabe and Sallie Ford from left to right: Photo by Autumn Andel“It’s a very inviting community,” Ford says.

Natasha Kmeto, Lewi Longmire, Jose Medeles, Tope, Skip vonKuske, Zia McCabe and Sallie Ford from left to right: Photo by Autumn Andel“It’s a very inviting community,” Ford says.

“It’s been going on here for a long time,” Longmire describes, “that there’s been a certain kind of support.”

“Once you’re in that pocket, people really are supportive,” Tope says. “People are open to collaborate and interested in jumping on other people’s records.” His forays into the indie rock world have definitely “opened up the door for more cross-genre collaborations.”

“For the most part, musicians are really friendly to each other and it’s more about playing shows with your friends,” Ford explains (which can also explain the proliferation of side projects and collaborations in town).

“There are a lot of individuals but it’s a wonderful, big hive-mind when it comes to playing together,” vonKuske says of his experience making music in Portland. Continuing his apian metaphor, vonKuske’s favorite thing about Portland’s music scene is the “cross pollination—just the willingness and openness of people to play music together.”

“People are open to a lot of ideas and they’re not closed off,” Tope adds.

One after another, musicians say: “There’s not a lot of ego involved. It’s more about having fun and making good music,” Ford adds.

“It’s not the me show,” Medeles says, while vonKuske believes, “Largely, there’s no self importance in it.”

“It’s easy to get excited because it’s one of the greatest woodshed towns there ever was,” vonKuske continues. “You can learn about your music [everywhere], and when you take it out, people are really excited to see what’s coming out of this city.”

“It’s the people and the level of excitement for art and for engaging in community—that’s the most exciting thing,” Kmeto summarizes.

“Everything goes. I don’t think that there’s anything against the rules in the Portland music scene,” McCabe says. “It really all exists here. There are a thousand niches in the Portland music scene and that is, to me, the most spectacular quality.”

For Kmeto and Tope who are seeking more diversity in the Portland music scene, one thing bodes well for them: “It feels like it’s always pulsating and moving forward and never stagnant,” Medeles says—which perfectly captures the vibrant music scene that exists in Portland today.

Lead image by Portland photographer and videographer Autumn Andel.